La schwannomatose

Schwannomatosis

What is schwannomatosis?

As the actual name implies (a previous underused name was NF3), schwannomatosis is characterized by the development of multiple noncancerous (benign) tumours called schwannomas, which are tumours of the tissue that covers nerves, usually on peripheral nerves and spinal nerves. It affects around 1 in 70,000 people at some point in their lifetime. Up to one third of patients show segmental schwannomatosis, confined to one limb or few adjacent spinal segments. Cranial nerve involvement is uncommon, most commonly on the trigeminal nerve. Meningiomas (a type of benign brain tumour) and unilateral vestibular schwannoma (a tumour from the balance branch of the acoustic nerve supplying the inner ear) can occur, with a substantial overlap with NF2 and a misdiagnosis of at least 9% of cases.

The absence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas (schwannomas affecting both hearing nerves) is the clue for the differential diagnosis from NF2. Symptom onset is typically after the age of 30. The distinctive hallmark is neuropathic pain, usually disproportionate to the size of the tumours. The intensity and frequency of pain varies significantly among individuals. Pain can be intractable, disabling and resulting in a diminished quality of life.

What causes schwannomatosis?

Mutations in SMARCB1 and LZTR1 can cause schwannomatosis. The proteins produced from both genes are thought to act as tumour suppressors, which normally keep cells from growing and dividing too rapidly or in an uncontrolled way. Mutations in either of these genes may help cells grow and divide without control or order to form a tumour. SMARCB1 and LZTR1 are located on chromosome 22q, near the NF2 gene. Meningiomas can occur in SMARCB1-related schwannomatosis, whereas unilateral vestibular schwannoma may occur with LZTR1-related schwannomatosis. Current genetic testing does not reveal a mutation in all affected individuals, and there may be additional genes responsible for the disorder in some people yet to be discovered.

How is schwannomatosis inherited?

The genetics of schwannomatosis is complex and remains incompletely understood. Studies suggest that 15 to 25 percent of cases of schwannomatosis run in families. These familial cases have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, which means a mutation in one copy of the SMARCB1 or LZTR1 gene in each cell greatly increases the risk of developing schwannomas. However, some people who have an altered gene never develop tumours, which is a situation known as reduced penetrance. New alterations occurring in sperm or eggs can end up in every cell of the child and represent approximately 30% for LZTR1-related schwannomatosis and 10% for SMARCB1-related schwannomatosis. Familial occurrence is inexplicably uncommon.

What are the surveillance options?

The general rule is observation, with annual imaging of intracranial and spinal tumours, as they can potentially cause spinal cord compression. Surgery is indicated for schwannomas associated with uncontrolled localized pain or neurologic deficits. It is important that surgery be performed in conjunction with ongoing pharmacologic pain management, as pain relief following tumour resection is not ensured. Overwhelming pain remains the primary clinical problem and need a comprehensive, multimodal approach to pain management, guided by a pain management specialist. Referral to mental health professionals is needed for anxiety and/or depression. Meningioma treatment is the same as for sporadic meningioma. Malignancy remains a theoretical risk especially in individuals with a SMARCB1 pathogenic variant.

Clinical practice guideline

Currently unavailable

Care pathway

Care pathway - Schwannomatosis (SCWN)

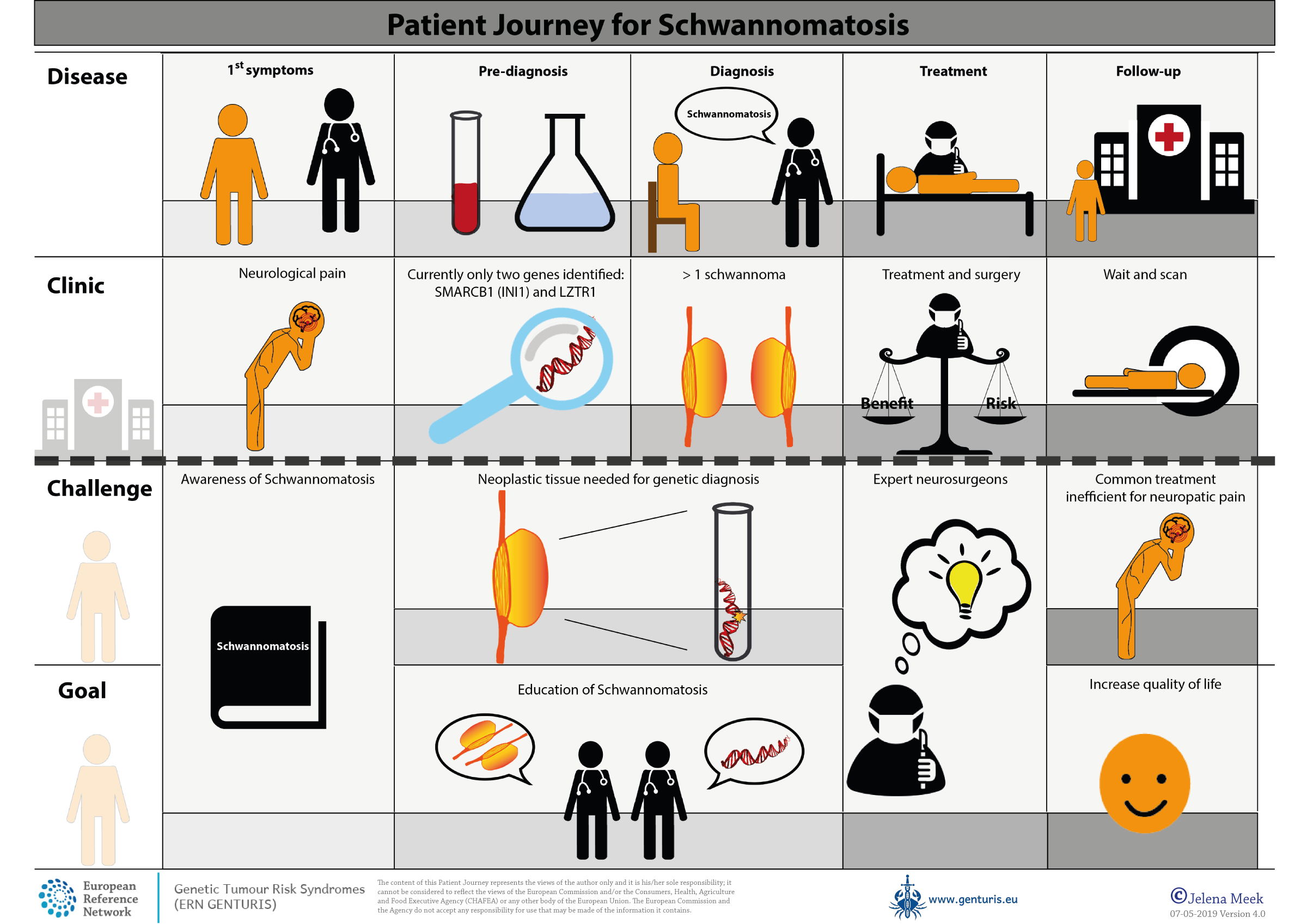

Patient journey